Contextualizing the Uganda-Tanzania war in Clausewitz’s theory of the trinity seeks to analyze how the Ugandan and the Tanzanian people, the political leadership and the military juxtaposed with the elements in the theory. According to Clausewitz (1832), the theory of the trinity exists in three dimensions –the primordial (hatred, enmity) – the people among whom exists a passion that blazes up in war; the passion inherent in the people. The passion that blazes up in war acts as the objective conditions of the war. In addition, the military as an element of subordination and an instrument of policy is subject to pure reason.[1]

Another element exhibits the scope and play of courage and talent in the realm of probability and chance. The scope of play of courage and talent in the realm of probability and chance depends on the character and ingenious of the commander and his army, while the political aims are a business of governments. The last element is the government, which not only provides the object of war, but also tames the irrational nature of the military into a rational one; the government that weighs and calculates options and objectives to be achieved. War should not be perceived as a pastime; it is no mere joy in daring and winning, no play for irresponsible enthusiasts.[2]

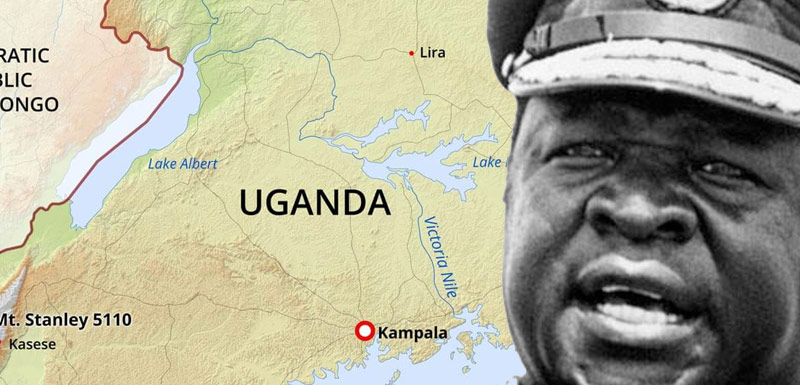

Clausewitz’s theory of the trinity if mirrored in Amin’s employment of the armed forces as an instrument of policy, one discovers that the military was not subordinate to the politics, and hence lacked guidance. As soon as Amin took over power in the bloody coup of 1971, he swept political activities under the carpet. Politics became the first casualty of his administration. Ironically, his hatred of politics and love for political power depicted him as shrewd political opportunist. During his maiden speech to the nation he said; “Fellow countrymen…I am not a politicians, but I am a professional soldier. I am, therefore, a man of few words and I shall be brief.”[3]

By declaring that he was not a politician but rather a military man, Amin abdicated his political role, and whatever decisions he made as a Head of State, he did so as a military general. His failure to draw a distinction between politics and the military in the long run left the military the dominant player. Accordingly, Amin placed a premium on the military –suspending decision-making organs of government like the Legislature and the Executive, and empowering the military decision-making organs to take political decisions. Even then, the Defence Council (DC) which he formed in 1973 remained ineffective. Both the Cabinet and DC simply existed in name.

The failure by the government of Uganda to define the political objectives, kept the military in the dark. Uganda’s political objectives in the war remained unclear. General Amin focused on limited objectives –preserving his power and minimizing dissent fomented as a result of his bad leadership. Attacking the Kagera Salient remained far beyond national interests.[4]

On the other hand, Nyerere ensured the military remained subordinate to the political authority. Its engagement in war remained purely for national strategic objectives. Much as Tanzania had limited objectives in the initial phase of the war –to punish Idi Amin for his irresponsible and reckless behavior, it had residual options to overthrow him at the table. To pursue such options required strategic guidance, and the understanding of the regional and global dynamics.

The second element of the trinity is the primordial violence –objective condition prevalent in the two countries. Amin’s brutal killings and destruction of property caused widespread resentment and condemnation in Tanzania. Following the attack on the Kagera Salient, the Tanzanian people raged against Amin. Nyerere’s political rhetoric inspired the Tanzanian people to rally behind Nyerere in the national effort to liberate their country. Youths, women and men of all walks of life enlisted in the military service, while the business men and the civilians contributed money, vehicles, produce and animals in support of the war effort.

In Uganda, Amin had antagonized Ugandans by killing, kidnapping and looting their property. Those who could not brave his regime ran to exile to join the liberation efforts. So, in reality, while the Tanzanians fought alongside their army, in Uganda, the civilians alienated Amin and his soldiers.

The third element is the play of courage and talent in the realm of probability. The scope for the play of courage and talent depends on the character and ingenious of the commander and his army, while the political aims are a business of government. Amin’s political leadership limited the scope for the generals and soldiers to play freely in the realm of probability and chance; in other words, the art of the General and operational art that not only translates the strategic intent into winnable concepts, but guarantees the support and sustainability of objective force in the field.

The roaming spirit depends on the quality and knowledge of the Generals and commanders. Since most of the Amin’s Generals and commanders were illiterate, their ability to contextualize the war situation remained wanting. Their decision-making was overloaded by the TPDF’s ingenious in form of operational art. The TPDF balanced employment of weapons, the use of indirect fires, better tactics –deception, ambushes and envelopment, quenching the spirit of resistance and resilience among the UA.

In conclusion, Clausewitz’s theory of the trinity provides a framework for the analysis and contextualization of the Uganda-Tanzania War. Looking at the protagonists, it is concluded that the Tanzanian political and military leadership considered the war as one coin with different sides and roles. Amin and his Generals pursued individual interests, obscuring Jomini and Clausewitz description of war and its object, and the understanding that the military exists for nothing but achieving the national political objectives.

[1]. Clausewitz (1832), p. 89).

[2]. Clausewitz (1832), p.27

[3]. Uganda Argus, 26, 1971.

[4]. Nyerere, following Amin’s attack on Kagera, said Amin had no any sound reason to attack Tanzania.

Colonel Charles Kisembo is currently doing his Doctor of Arts in Military History at Warnborough College Ireland.

All views expressed are those of the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Warnborough College Ireland.